On August 29, 1919, the Belgian parliament passed the Vandervelde Law , a milestone in Belgian alcohol legislation. Named after socialist Emile Vandervelde, the law prohibited the sale and consumption of spirits in cafés, hotels, train stations, and other public places. Anyone wishing to buy spirits had to purchase at least two liters at a time. Moreover, excise duties quadrupled, significantly increasing the price of spirits.

At first glance, it seems as if the socialists were completely against alcohol with this law. But was that really the case? In 1913, Vooruit launched its own pilsner, Triomfbier, for the World's Fair in Ghent. Other cooperatives followed suit. At the same time, serving alcohol was prohibited in many social houses. This apparent contradiction dates back to the 19th century, when socialists drew a sharp distinction between beer and spirits.

Beer was considered a respectable, even healthy, beverage. Because it spoiled quickly, it was brewed locally and was difficult to transport, making it a modestly profitable product. Spirits, on the other hand, were cheap to produce, easy to transport, and yielded enormous profit margins. The government also benefited: in Belgium, 15% of state revenues in the 19th century came from taxes on spirits. This was seen as a "misery tax" that primarily affected workers, plunging them into financial and social misery.

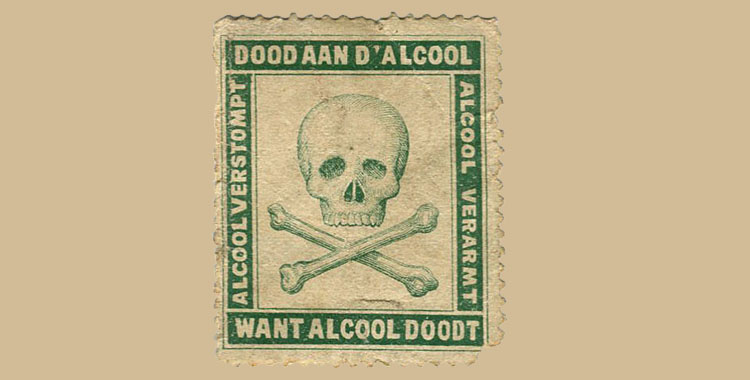

Socialists therefore actively campaigned against distilled beverages. Spirits were banned in their houses of worship, and they founded temperance and teetotalism associations, such as the Ligue Socialiste Antialcoolique (Socialist Anti-Alcoholic League) and the socialist Good Templars. Emile Vandervelde supported these initiatives both in Belgium and within the Second International. With success, because after the law's introduction, spirits consumption fell dramatically, while beer production and consumption flourished.

The socialist attitude toward alcohol was therefore not black and white. Beer remained an acceptable popular drink, while spirits were opposed as a source of exploitation and misery. Thus, the "tournée minérale" (mineral tour) was, in a sense, put into practice early on—but never completely.