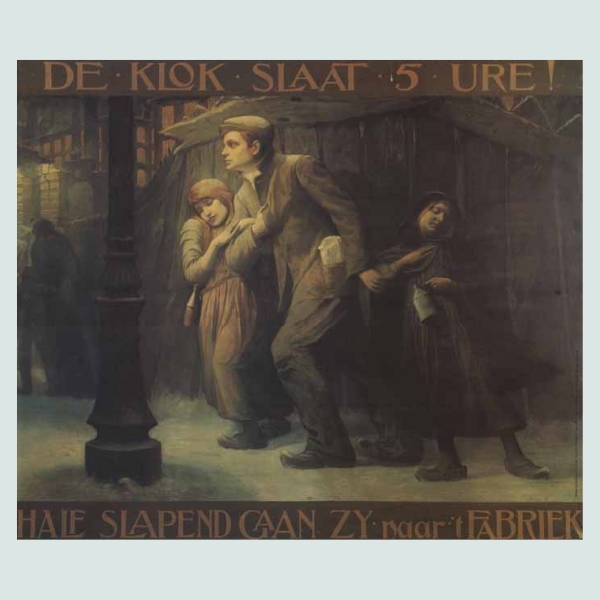

In het licht van een straatlantaarn toont het een man die voor dag en dauw naar de fabriek trekt. Zijn dochters, kinderen nog, hangen half slapend aan zijn arm, op houten klompen en nauwelijks beschermd tegen de kou. De tekst boven en onder het schilderij laat aan duidelijkheid niets te wensen over. Het is een scherpe aanklacht tegen de erbarmelijke levensomstandigheden van de arbeiders, in het bijzonder tegen de extreem lange werkdagen, twaalf uur per dag of meer, en tegen de schandelijke kinderarbeid.

In het midden van de negentiende eeuw was er van sociale wetgeving geen sprake, de arbeiders waren volledig overgeleverd aan de willekeur van de patroons. Om min of meer rond te komen, en dan nog, moest het hele gezin, kinderen inbegrepen, van ’s morgens ontiegelijk vroeg tot ’s avonds laat, gaan werken in de fabriek.

Van bij haar oprichting in 1885 streed de socialistische partij tegen deze uitwassen van de industrialisatie. Kinderarbeid werd moeizaam en met veel tegenkanting van de conservatieve katholieke partij ingeperkt en uiteindelijk afgeschaft. Een eerste wet in 1884 verbood arbeid in de mijnen voor jongens onder de 12 en meisjes onder de 14 jaar. In 1889 werd alle industriële arbeid voor kinderen onder de 12 jaar verboden, in 1914 uitgebreid tot kinderen onder de 14 jaar.

Het schilderij hing bijna een eeuw lang naast het podium in de grote zaal van Ons Huis op de Vrijdagmarkt, het kloppend hart van de socialistische beweging in het Gentse. Het werd een waar icoon van de arbeidersbeweging en haar strijd voor verbetering van de levensomstandigheden. Als tableau vivant werd het uitgebeeld in stoeten en massaspektakels. Reproducties sierden jarenlang talrijke arbeiderswoningen. Vandaag vind je het schilderij in Floréal in Blankenberge.